A Life in Art, Science, and Stillness: Giovanna Garzoni

Giovanna Garzoni was born in 1600 in Ascoli Piceno, a town in Italy’s Marche region. It’s believed that her maternal uncle may have been her first drawing teacher. As a child, she moved with her family to Venice, where she continued her studies in oil painting—likely under Palma il Giovane, the city's leading painter after Tintoretto's death. His influence is evident in her early stylistic choices.

In Venice, she also learned the art of miniature painting. Her earliest examples—featuring flowers, birds, and insects tucked into the initials of texts—appear in the Libro de’ caratteri cancellereschi corsivi, a collection of 42 folios.

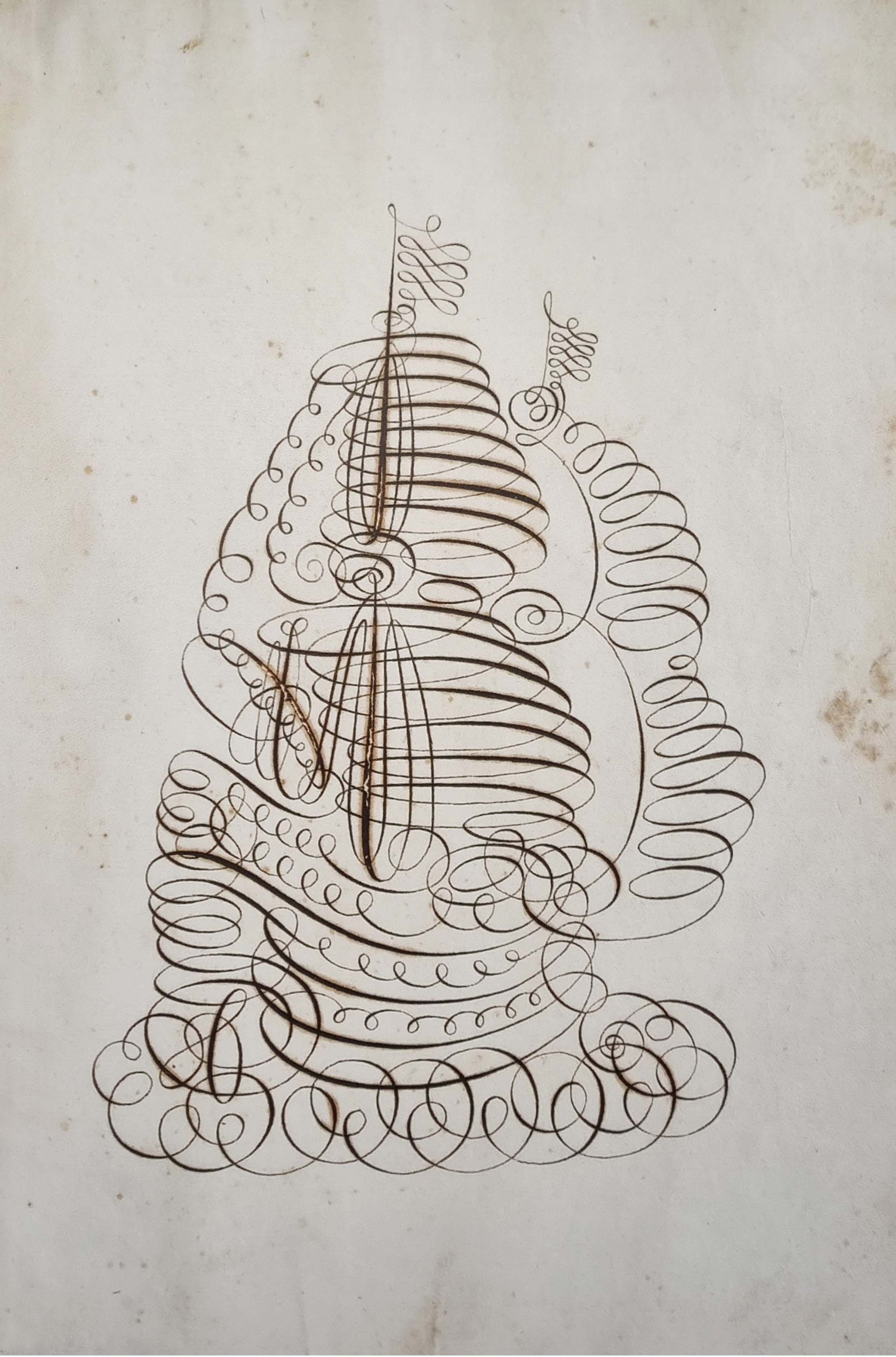

Giovanna was also an accomplished calligrapher, having studied Italic (or corsivo) lettering from a 1605 Dutch manual by Jan van de Velde the Elder. From the same book, she copied Galleon at Sea, a continuous-line drawing of a ship sailing through the foaming sea, that prophetically echoes her future travels across Europe.

Giovanna Garzoni, Galleon at Sea, in 'Libro de’ caratteri cancellereschi corsivi', 1616-1622. Accademia Nazionale di San Luca, Rome

The Libro de’ caratteri is crucial for understanding her beginnings as, alongside her calligraphy exercises, it includes draft letters to aristocrats and potential patrons, evidence of her ambition to enter elite European courts.

During her first stay in Florence (1618–1621), Giovanna painted Self-Portrait as Apollo. She was at the court of Grand Duchess Maria Maddalena, where she met Artemisia Gentileschi—whom she would encounter again in Venice, Naples, and London—and Arcangela Paladini, a fellow artist of her generation. It was likely here that she also met Cassiano dal Pozzo, antiquarian and secretary to Cardinal Francesco Barberini. These influential figures may have encouraged her to pursue a professional career in art.

Giovanna Garzoni, Self-Portrait as Apollo, ca. 1618-1620. Palazzo del Quirinale, Rome

In Self-Portrait as Apollo, she wears a laurel wreath and holds a viola da gamba, echoing earlier self-portraits by Sofonisba Anguissola, Lavinia Fontana, and Artemisia Gentileschi. Her musical talent had been celebrated since childhood, and like Venetian predecessors Irene di Spilimbergo and Marietta Robusti (Tintoretto’s daughter), she studied both painting and music to secure court patronage.

Giovanna returned to Venice in 1622 and married portraitist Tiberio Tinelli. The marriage was annulled two years later in 1624. A video about the marriage, its annulment, and the tale of a flower, a fruit, and a curse is available in the “Taking It Further” section at the end of this essay.

Around this time, the 3rd Duke of Alcalá, on his return to Spain from Rome, encountered Giovanna’s work in Venice. In 1629, now appointed Viceroy, he invited her to Naples. She moved there the following year, accompanied by her brother Mattio.

Between 1631 and 1632, Giovanna traveled frequently between Naples and Rome. Thanks to Cassiano dal Pozzo, she gained access to the Accademia dei Lincei and the Syntaxis Plantaria, a scientific collection of botanical illustrations. This was pivotal in shaping her observational and scientific approach to art.

Giovanna Garzoni, Colocasia antiquorum, from 'Piante Varie', ca. 1630-1632. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library, Washington, DC

During this time, she also created Piante Varie, a series of 50 watercolour plant studies for naturalist and pharmacist Francesco Corvino. Her precise miniature painting technique—applying tiny tempera dots with a magnifying glass—was now combined with scientific accuracy, possibly enhanced by early microscopes from the Lincei circle.

Among these works, Colocasia antiquorum stands out. One of only two exotic plants in the series, it features her elegant calligraphy—Aro egizio—beside the root. Another inscription, added in the 18th century, appears in the upper right corner.

Giovanna’s contributions to scientific illustration are widely recognized. Her early Roman work marks her adoption of traditional botanical illustration conventions. Yet, her characteristic attention to detail, curling leaves, and vibrant palette make her work uniquely expressive.

From 1632 to 1637, she worked at the court of Vittorio Amedeo I of Savoy and Christine of France in Turin. Though once thought that Cassiano dal Pozzo arranged this, a letter from Christine herself to the Savoy ambassador in Rome confirms that the Duchess personally requested Giovanna’s presence. At 32, Giovanna received a generous salary as “miniatrice di Madama Reale” (miniaturist to the Royal Madam), although few works from this period have survived.

Giovanna Garzoni, Portrait of Caterina Micaela, Duchess of Savoy, 1632-1637. Uffizi Gallery, Florence

Following the family tradition of inserting family portraits into decorative schemes, Christine commissioned posthumous portraits of of Emanuele Filiberto, Carlo Emanuele I, Caterina Michela (Carlo Emanuele I’s wife), and Vittorio Amedeo I for the Valentino Castle. Giovanna reinterpreted earlier portraits, placing subjects close to the picture plane and changing their attire. Her vibrant colours and jewel-like rendering show the influence of François Clouet and the Valois tradition of female artistic patronage.

Christine’s predecessor – Margherita di Valois – had very likely seen and admired François Clouet's pastel portraits while visiting the Valois court of Caterina de’ Medici. Calling Giovanna Garzoni at the court of Savoy may have been a way of continuing this female taste tradition.

After the duke’s death in 1637, power struggles made court life less secure, and Giovanna left Turin in 1638. However, Christine’s support continued to open doors for her abroad—in England and France—where Christine’s sister and brother, Queen Henrietta Maria and King Louis XIII, welcomed her.

In England (1638), traveling with Artemisia Gentileschi and her brother Mattio, Giovanna painted a (now lost) portrait of the Savoy ambassador and studied Dürer’s drawings in architect Inigo Jones’s collection. In her Lioness with an Open Eye, she completed missing elements of Dürer’s original and added whimsical touches, such as a smiling face and alert gaze.

Giovanna Garzoni (after Albrecht Dürer), Lioness with an Open Eye, ca. 1639. Accademia Nazionale di San Luca, Rome

By 1640–1641, she was in France, where she painted a miniature of Cardinal Richelieu. The support of Henrietta Maria and Christine likely eased her access to the royal court. Still, Giovanna yearned for Italy, disliking “i costumi di Francia” (French customs). She contacted the Medici court via their Paris ambassador and returned to Italy in 1641.

Before settling again in Florence, she worked briefly in Rome for Anna Colonna, wife of Taddeo Barberini. Colonna was one of Giovanna’s most loyal patrons, perhaps even more so than Artemisia Gentileschi.

In 1642, Giovanna began her second and longer stay at the Medici court in Florence, lasting until 1651. Grand Duke Ferdinando II had married Vittoria della Rovere, who held Garzoni in high regard. The artist had unprecedented access to the Medici collections and was even allowed to borrow Raphael’s Madonna della Seggiola from the Uffizi’s Tribuna to copy at home—something never permitted before.

Copying Old Masters was a popular practice in 17th-century Florence. Giovanna’s miniature version of Raphael’s painting (measuring just 24 x 24 cm) softens the features of the Virgin and Child using delicate hatching and dotting. While once viewable only under magnification, her technique now invites viewers to zoom in digitally to admire every detail.

Giovanna Garzoni (after Raffaello), Madonna della seggiola, 1649. Galerie Charles Ratton et Guy Ladrière, Paris

Garzoni’s botanical illustrations for the Medici family are equally distinctive. In her Carte di semplici series, plants are depicted with imperfections, asymmetry, and paired unexpectedly with insects or fruits.

In the example below, a hyacinth is surrounded by cherries, an artichoke, and a lizard—elements that have no real connection with it. These extras are not exactly background actors, because often there is no proportion between them. Also, the contrast between the frontal shadeless depiction of the main species, and the more real representation of the fruits, animals or insects creates optical illusions.

A case in point is the lizard that, covering part of the plant's roots, looks like it’s crawling on the parchment.

Giovanna Garzoni, Hyacinth with Four Cherries, a Lizard, and an Artichoke, ca. 1648. Uffizi Gallery, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe, Florence

This choice of support goes hand in hand with Giovanna Garzoni's minute painting technique.

She painted on parchment, a surface that enhanced detail and light reflection—what some call “white glowing parchment.” Though “miniature” implies small size, in Italian, miniare means “to illuminate,” referring to the red pigment used on parchment, not dimensions.

Giovanna Garzoni, Vase with Flowers on a Stone Plinth with a Peach, ca. 1647. Uffizi Gallery, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe, Florence

Her Vase with Flowers on a Stone Plinth with a Peach (65 x 47 cm) is a large work featuring a variety of flowers in a buffone vase. The flowers spill out in every direction, accompanied by insects. The bouquet includes local blossoms like roses and lavender alongside exotic species such as Mexican marigold and Japanese morning glory. A peach on the plinth adds yet another international touch, reflecting the Medici’s global reach.

The choice of which vessel to use is always important in Giovanna’s still-lifes. In this instance, the buffone vase is instrumental in producing a stark contrast between the sameness of the stems and the variety of the flowers. In addition, on the buffoon vase is reflected a window—a motif popular in many paintings of the time, especially from Northern Europe which Giovanna may have seen and studied during her international travels of the 1630s and 1640s.

Flemish still-life painting may have influenced Giovanna's choice of subjects and her style at large, but what is new in this work is that the window is reflected three times and that the light, coming in from the window, appears on the lateral walls too. This detail may be just another sign of Giovanna’s interest in the fields of optics and lens production.

Giovanna Garzoni, one of the first women artists to practise the art of still-life, contributed greatly to the genre. It is safe to say that the genre has never been highly regarded. According to some art historians this low regard corresponds to the low status of women as women artists made a distinctive speciality of the genre. And yet, important contemporary male artists had produced drawings for important botanical texts. For instance, the work Flora overo cultura di fiori, published in 1630 by the Jesuit Giovan Battista Ferrari, had prints after drawings by Pietro da Cortona, Andrea Sacchi, and Guido Reni.

Giovanna Garzoni’s life experiences and exchanges result in the distinctive way objects are assembled and displayed in her still-lifes. Staying at different European courts allowed the artist to study and examine rare specimens from private Wunderkammers. Similarly, getting in contact with people from all over the world sparked her interest in how people, objects, and ideas travel.

Giovanna Garzoni, Dog with a Biscuit and a Chinese Cup, ca. 1648. Uffizi Gallery, Palatine Gallery, Florence

Dog with a Biscuit and a Chinese Cup—signed “Giovanna Garzoni F.” (for fecit)—was painted for Vittoria della Rovere. As seen in some portraits by Lavinia Fontana, small dogs were expensive accessories, and sometimes they would themselves be portrayed adorned with luxurious ornaments such as sparkling collars and earrings. But here the focus is an old English pug with a simple bell collar, resting peacefully beside two biscuits and a Chinese porcelain cup. Rather than the dog eating the biscuits, flies nibble them, suggesting restraint and tranquility.

The grey-blue slipware cup, used for sipping hot chocolate, references international trade. Like the dog, which originated in China, the cup underscores the Medici’s cosmopolitan tastes. Garzoni admired Chinese painting traditions, especially in botanical and still-life genres, where women artists also excelled.

In 1651, Giovanna Garzoni moved to Rome but kept working for the Medici family who would provide specimens from their collection. The artist kept painting miniature copies of older masters, and flower still-lifes for Vittoria della Rovere.

The Grand Duchess, who among other things was passionate about floriculture, covered her favourite residence, the Villa di Poggio Imperiale, with flower still-lifes. She also collected in one single dedicated room—the Stanza dell'Aurora—all the works that Giovanna had painted for her and her husband the Grand Duke Ferdinando II—namely a series of twenty still-lifes painted between 1655 and 1662.

Giovanna Garzoni, Plate with Cherries and Carnations, ca. 1655-1662. Uffizi Gallery, Palatine Gallery, Florence

Plate with Cherries and Carnations is part of the aforementioned series and ties in with a still-life discussed previously.

Giovanna’s first documented still-lifes are the ones painted during her sojourn in Turin working as a miniaturist for Christine of France, duchess of Savoy. Although very few miniatures from this period survived, we do know that Giovanna studied and took inspiration from Lombard and Flemish examples in the Savoy collection. It is worth noting that contemporary inventories list several Fede Galizia’s still-lifes among the Lombard works.

Fede Galizia, Still Life of Cherries in a Bowl, ca. 1610-30. Royal Collection Trust, London

Giovanna’s stylistic and technical approach to the genre differs, of course, from that of Fede Galizia. Whereas Galizia’s still-lifes have a tactile quality, Giovanna uses a technique that, giving the illusion of looking at nature through an optical lens, makes the picture plane recede.

In most of her compositions, as in the one presented here, Giovanna focuses on presenting one single species in a vessel, together with one or two elements from another genre (flower, fruit, or animal) as ornaments displayed on the base of support.

The single species is shown in the middle of the foreground in a single dish, vase, or bowl that stands on what became one of Giovanna’s trademarks—a brownish, amorphous ground executed with her minute technique of painting dots close to one another.

The ground has the effect of toning down the brightness of the background and the luminosity of the fruit, in this case the cherries piled up on a simple plate.

For those who intend to explore the genre further, it might be useful to know that what Dutch and English would call ‘stilleven’ or ‘still life’ becomes ‘natura morta’ and ‘nature morte’ in Italian and French respectively.

The term ‘stilleven’ to indicate the representation of still nature as opposed to that of men and animals, made its first appearance in the Dutch inventories only after 1650, whereas in Italy the term ‘natura morta’ appeared at the end of the seventeenth century and in France during the eighteenth.

So how would Giovanna Garzoni have referred to her paintings? She would have simply described the subjects and say “a painting with cherries and carnations”, “a painting with figs and snail” and so on. But that would be just for the best, considering that the Italian ‘natura morta’ translates ‘dead life’ and, as seen in Plate with Cherries and Carnations, Giovanna's fruit is not ‘dead’ at all.

Looking closely at Giovanna's compositions, it becomes apparent that the central parts are larger and rounder. In Plate with Cherries and Carnations, for instance, the curve outlines seem to animate the cherries. Giovanna Garzoni believed in animism, and for those who’d like to explore this aspect I’ve included some interesting links in the ‘Taking it further’ section.

Carlo Maratta, Portrait of Giovanna Garzoni, ca. 1665. Pinacoteca Civica, Ascoli Piceno

This portrait, painted by the renowned artist Carlo Maratta five years before Giovanna’s death, served as model for the portrait donated to the Accademia di San Luca and the one on the funerary monument in the Church of Saints Luca and Martina in Rome.

Giovanna Garzoni had joined the Accademia di San Luca in 1651 as ‘accademica di merito’. That means the artist had been accepted but not ‘registered’. Only ‘registered’ artists were allowed to attend the so-called accademie—that is meetings, and lessons.

Since 1607 the Accademia di San Luca had given the 'accademica di merito' title to women artists with Lavinia Fontana being the first to be accepted. As the title was only an honorific, perhaps it was just a way for the Accademia to associate the institution to famous women painters. A sign of admiration surely was the collecting of portraits of women artists, from Properzia de’ Rossi to Sofonisba Anguissola, Lavinia Fontana, and Elisabetta Sirani.

In this portrait, which is exhibited in Ascoli Piceno where the artist was born, Giovanna Garzoni is wearing sombre clothes, the most suitable to a widow, and holding the portrait of a young woman who could be herself or Christine of France, Duchess of Savoy—her first distinguish female patron.

In addition to the regular donations she used to make to the Accademia di San Luca, Giovanna Garzoni left to the institution her house and a fund.

The house, not far from the original Accademia building in Via Bonella, was demolished in 1934 when via dei Fori Imperiali was built.

Giovanni Antonio Canal called Canaletto, The Arch of Septimus Severus in Rome, ca. 1743. Cincinnati Art Museum

It is visible, though, in this view by Canaletto, the eighteenth-century Venetian painter, of the Arco di Settimio Severo. Looking towards the Campidoglio, the painting features on the left the Church of the Saints Luca and Martina and, built just up against its right wall, Giovanna Garzoni's house.

What is still left is the funerary monument on the counter-façade of the church.

Taking it further

On Giovanna Garzoni ’s Venetian heritage

Athena Art Foundtion | Overlooked Art History | Giovanna Garzoni: 17th-century still life artist and miniaturist | Video

On Garzoni’s marriage to Tiberio Tinelli and following annulment together with the tale of a flower, a fruit, and a curse

Save Venice | Education & Enrichment Series | Giovanna Garzoni: a Woman Artist and Musician in 17th-Century Venice | Video to minute 43.50

Dumbarton Oaks Research Library, Washington, DC

Digitised Rare Books | Garzoni, Giovanna, 1600-1670. [Piante varie]. [ca. 1650]

Sheila Barker (ed.), “La grandezza del universo” nell’arte di Giovanna Garzoni / “The grandeur of the universe” in the art of Giovanna Garzoni. Exhibition catalogue. Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Palazzo Pitti, 2020.